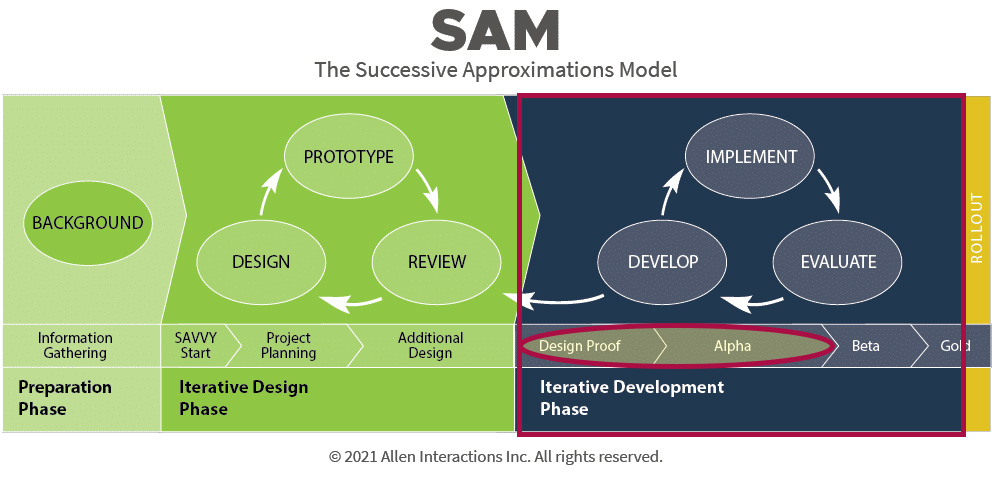

Overall, this project is in the iterative development phase of the Successive Approximations Model. Many learning modules are in the alpha prototype phase. Some have reached beta status and are currently being tested.

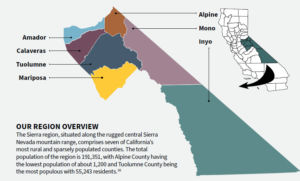

The Sierra Region; PC: California Jobs First Sierra Region

The Sierra region faces both volunteer and paid EMS provider shortages. There are many challenges resulting in these shortages, including limited technology resources, limited funding, large travel distances, and workforce burnout. EMS training is often cost-prohibitive when factoring in tuition, books, background checks and medical examination requirements for clinical/field internship eligibility, and travel expenses.

According to the CDC (2024) and Rural Health Information Hub (2023), community paramedicine programs reduce rural mortality by bringing healthcare directly to communities. EMTs, AEMTs, and paramedics are essential to these programs, yet the Sierra region struggles to fill even paid EMS positions.

King et al. (2018) highlight that rural healthcare scarcity leads to life expectancies 2.5 years shorter than urban areas, exacerbated by reliance on volunteer EMS. In some areas, the difference is as significant as 20 years. Volunteer shortages, driven by training costs, leave communities vulnerable. Strengthening volunteer services, coupled with training laypeople through courses like Emergency Medical Responder and Wilderness First Responder, equips communities with critical skills to stabilize patients until EMS arrives.

Current barriers to EMS training include cost, travel, and inflexible schedules, particularly for working adults. This program addresses these challenges by offering a multi-level hybrid model with online and in-person components tailored for rural areas.

- Emergency Medical Responder/Wilderness First Responder Combo

- No Pre-Requisite

- 40+ Hours Online Asynchronous Instruction

- 50 Hours In-Person Instruction

- Emergency Medical Technician

- Pre-Requisite: BLS for Healthcare Provider CPR certification

- Recommended Courses: EMR or WFR certification

- 80+ Hours Online Asynchronous Instruction

- 100 Hours In-Person Instruction

- 24 Hours Clinical Experience

- Advanced Emergency Medical Technician

- Pre-Requisite: EMT License, BLS for Healthcare Provider CPR certification, Anatomy and Physiology

- Recommended Courses: Medical Terminology, Pharmacology

- 40+ Hours Online Asynchronous Instruction

- 60 Hours In-Person Instruction

- 40 Hours Clinical Experience

- 40 Hours Field Internship

This project also aims to tackle systemic inequities. Rivard et al. (2021) report that EMS professionals are 85% white, while Rudman et al. (2023) cite low diversity in EMS as a barrier to equity. Inclusive curriculum materials and targeted recruitment will address representation gaps, particularly among Hispanic/Latino and American Indian populations, who comprise up to 27.4% of the Sierra’s demographic (United States Census Bureau, 2023). Outreach and accessible scheduling will expand healthcare career pathways, fostering a more diverse and resilient EMS workforce.

Historically, educational materials have lacked representation of marginalized groups. Medical images often depict white individuals, overlooking how conditions like shock, hives, or bruising appear on dark skin. This omission can lead to misdiagnoses and inadequate care.

The lack of representation of disinvested and marginalized groups has a negative impact on career choices. Morukian (2022) posits that it is more difficult for a person of color to see themselves as capable of advancing in a career due to the lack of role models. We need to have an EMS workforce that is more representative of the demographics in the Sierra, including American Indian and Hispanic/Latino populations, which make up 7.2% and 18%, respectively (United States Census Bureau, 2023). In some areas, these percentages reach up to 27.4%.

This project addresses inequity through inclusive curriculum materials and targeted recruitment. Curriculum materials will incorporate images and graphics representing disinvested communities and marginalized groups, educate on how medical signs vary across races, and highlight rural healthcare career pathways.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 16). The Value of Community Paramedicine. Retrieved December 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ems-community-paramedicine/php/data-research/community-paramedicine/index.html

King, N., Pigman, M., Huling, S., & Hanson, B. (2018). EMS Services in Rural America: Challenges and Opportunities. N. R. H. Association. https://www.ruralhealth.us/NRHA/media/Emerge_NRHA/Advocacy/Policy%20documents/05-11-18-NRHA-Policy-EMS.pdf

Morukian, M. (2022). Diversity, equity, and inclusion for trainers. Association for Talent Development.

Rivard, M. K., Cash, R. E., Mercer, C. B., Chrzan, K., & Panchal, A. R. (2021). Demography of the National Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Description of Those Providing Patient Care in the Prehospital Setting. Prehospital Emergency Care, 25(2), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2020.1737282

Rudman, J. S., Farcas, A., Salazar, G. A., Hoff, J., Crowe, R. P., Whitten-Chung, K., Torres, G., Pereira, C., Hill, E., Jafri, S., Page, D. I., von Isenburg, M., Haamid, A., & Joiner, A. P. (2023). Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the United States Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Emergency Care, 27(4), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2022.2130485

Rural Health Information Hub. (2024, August 29). Community Paramedicine. Retrieved December 12, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/community-paramedicine

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.) Profiles Results. Retrieved December 12, 2024. https://data.census.gov/profile?g=050XX00US06003,06009,06027,06043,06051,06097,06109

Several software applications are being used to develop this project. Select an image below to learn more.

Select a link below to review a prototype.